This decision concerns a method for providing an advance warning of the end of a commercial break. However, the Board did not grant a patent, because the distinguishing features were either considered a non-technical or an obvious technical implementation.

Here are the practical takeaways from the decision T 1553/18 (Broadcast content resume reminder/DISH) of February 8, 2023, of the Technical Board of Appeal 3.5.04.

Key takeaways

The invention

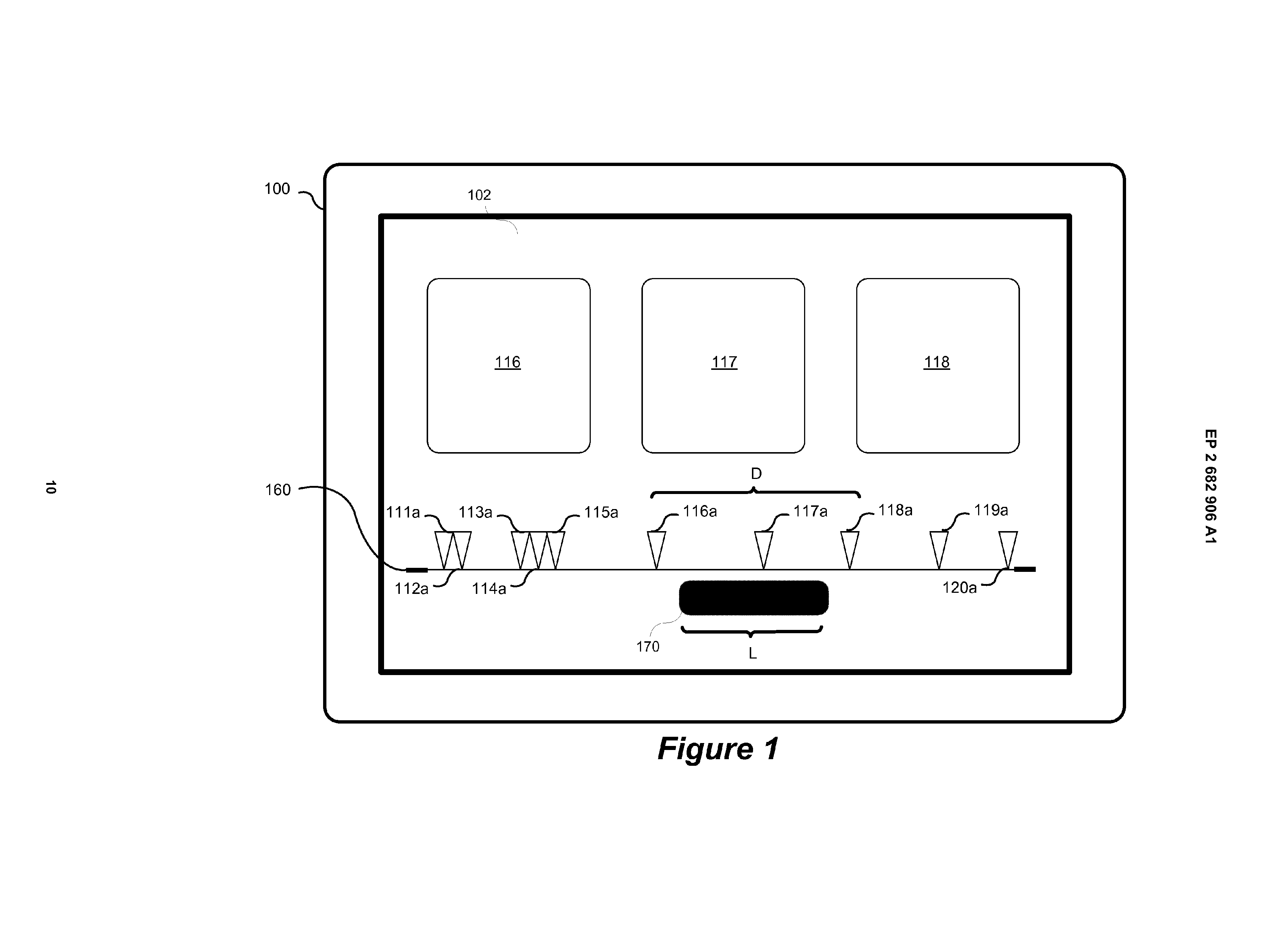

The invention relates to providing an advance warning of the end of a commercial break so that a viewer has enough time to switch back to the preferred programming and does not miss any of it once the commercial break has ended (cf., application , page 4, lines 1-8).

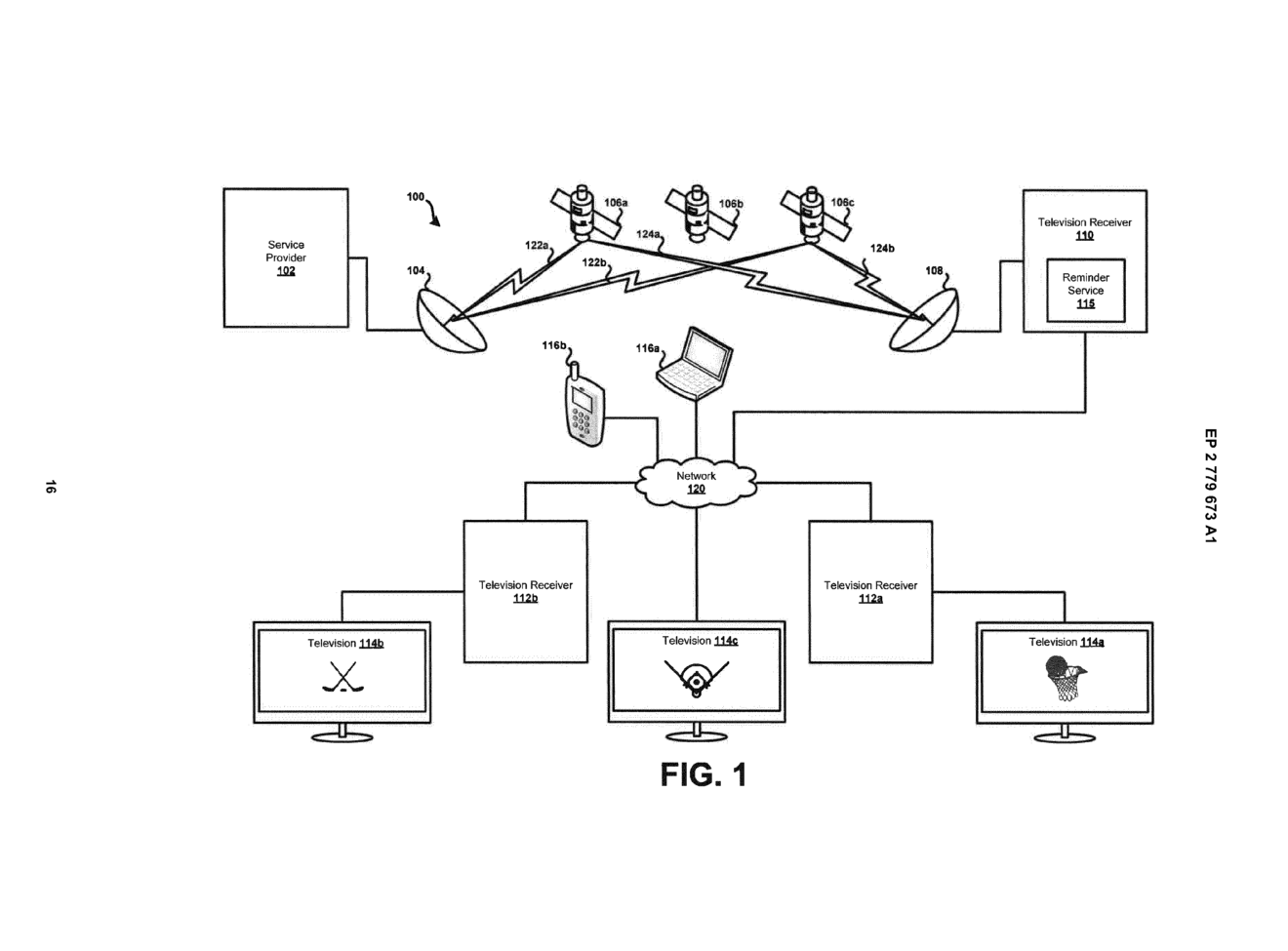

Fig. 1 of EP 2 779 673 A1

-

Claim 1 of the Main Request

Is it patentable?

Both the Board in charge and the Appellant agreed on D5 representing the closest prior art. Compared to the disclosure of D5, claim 1 of the main request differs in the following aspects:

-

- the monitoring of the status of the commercial break includes detection of timing information within a broadcast data stream of the channel associated with the particular broadcast programming (partial feature 3.);

- determining, prior to the ending of the commercial break, an upcoming ending time for the commercial break, based on the timing information (feature 4)

- determining, based on the timing information, a time for outputting an interface indicating the upcoming ending of the commercial break and outputting the interface at this time (feature 5 and partial feature 6)

With respect to the alleged technical effect, the Board stated:

A distinction between a “commercial break” and a piece of “particular broadcast programming” is not made by technical features. From the perspective of a user, a piece of “particular broadcast programming” is something potentially interesting (see claim 1, lines 6 to 7). In contrast, users change channels during commercial breaks, i.e. try to avoid spending time watching them (see description, page 1, lines 27 to 28).

What users are interested in is a subjective non-technical aspect. Contrary to the above assumptions, some users may be more interested in new and nicely made commercials transmitted during a respective break than in regular broadcast programming. Hence, to identify a transition point between a commercial break and the resumption of a particular broadcast programme serves a non-technical purpose, namely to maximise the time users spend watching content of interest to them.

The same holds for providing an advance warning of the end of a commercial break so that a user has enough time to switch back to the preferred programming and does not miss any of it once the commercial break has ended. This embodies the wish of a user not to miss any of the “particular broadcast programming” at the expense of watching the last moments of a commercial.

Hence, providing an advance warning of the end of a commercial break can be seen as an aim to be achieved in a non-technical field and may legitimately appear in the formulation of the objective technical problem (see Case Law of the Boards of Appeal of the European Patent Office, 10th edition 2022, I.D.9.2.6).

The Appellant argued:

None of the features in the claim were expressed as non-technical features and that, as a result, all the features should have been considered to have technical character contributing to inventive step. […] and that the claim did not address an aim in a non-technical field. The claim addressed a problem in the technical field of multi-channel video players, i.e. set-top boxes, and provided a viewer with improved control of the video stream sent to the display.

[In addition] the subject-matter of claim 1 did not relate to a method of doing business, i.e. obtaining revenues for the insertion of commercial breaks. The method defined in claim 1 set out a way to treat commercial breaks as they arrived as part of broadcast programming. In the method of claim 1, commercial breaks were simply another part of broadcast programming.

The Board was not convinced by these arguments and instead stated that:

The board takes the view that in all the distinguishing features quoted under point 2.3 above, the term “commercial break” appears. This term and its distinction from a piece of “particular broadcast programming” is inherently non-technical because it is founded on the subjective judgement of a user that the particular broadcast programming is something not to be missed, while watching commercials during a respective break is to be avoided.

It agrees that the subject-matter of claim 1 is not about obtaining revenues for the insertion of commercial breaks. However, the distinction between a “commercial break” and a piece of “particular broadcast programming” is non-technical. To reflect this distinction in the subsequent formulation of the objective technical problem, the board refers to a “particular broadcast programming” as preferred programming and to a “commercial break” as non-preferred programming.

As a result, the Board followed that the distinguishing features can be part of the formulation of the problem to be solved, namely:

How to implement an advance warning of the end of non-preferred programming so that a viewer has enough time to switch back to the preferred programming and does not miss any of it once the non preferred programming has ended. .

Accordingly, the skilled person in the art would have understood that to implement an advance warning of the end of non-preferred programming, the end time of the non-preferred programming had to be identified before it was over. This could not be implemented by an analysis of audio-visual content of the non-preferred programming. Such an analysis could only identify a change from non-preferred programming to preferred programming after the change had happened.

As documents D4 or D7 allegedly include corresponding hints for solving the problem, the Board concluded that the skilled person in the art would have arrived at all the distinguishing features in a straightforward manner.

Hence, the board finds that the subject-matter of claim 1 does not involve an inventive step within the meaning of Article 56 EPC.

More information

You can read the full decision here: T 1553/18 (Broadcast content resume reminder/DISH) of February 8, 2023, of the Technical Board of Appeal 3.5.04.

Max is a computer scientist and patent attorney trainee at BARDEHLE PAGENBERG. Due to his technical background, he specializes in prosecuting and litigating software patents, in particular algorithm based inventions.