The application relates to online payments, particularly by using the user’s device instead of the merchant’s PoS terminal. The Examining Division argued that the PoS configuration reflected merchant business rules and that deploying these to the user device was merely a straightforward implementation on a known payment system architecture. The Board disagreed and indicated that while the abstract aim of avoiding transmission of card data to the merchant may originate from the business person, the solution requires technical knowledge of the system architecture and falls within the expertise of the technically skilled person. Thus it was considered technical.

Here are the practical takeaways from the decision: T 1392/20 (User device configured to function as PoS terminal/HILLOA) of July 15, 2025, of the Technical Board of Appeal 3.5.01.

Key takeaways

The invention

The Application defined the invention as follows:

1.2 Typically, when making online payments, customers are required to provide their payment card data to the merchant, which poses a risk of fraud. On the one hand, customers may use stolen card data, which is a risk for the merchant. On the other hand, dishonest merchants may misuse the card data, which is a risk for the customer, [0003], [0004]. To address these issues, the invention suggests configuring a user device, such as a smartphone, to function as the merchant’s point-of-sale (PoS) terminal.

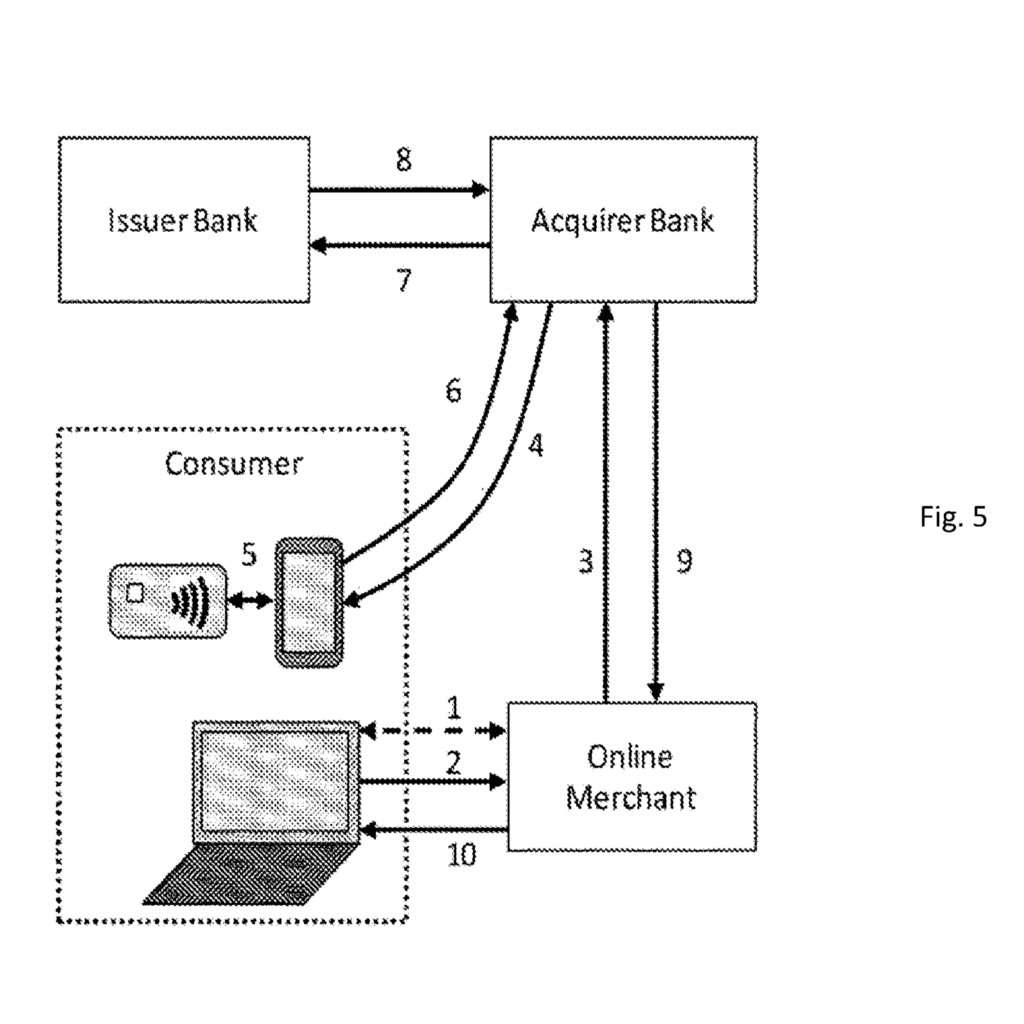

1.3 Looking at Figure 5 or 6, a user initiates (2) a payment transaction at a merchant’s website by providing an identifier of their user device. The merchant forwards (3) the identifier to a payment service host operated for example by an acquiring bank. The host retrieves a PoS configuration profile specific to the merchant and sends (4) a corresponding PoS configuration to the user device based on routing data stored in a user device profile. The user device configures a payment application according to the received PoS configuration and reads (5) a payment card using a card reader before processing the transaction, [0051] to [0056] and [0091] to [0099].

Fig.5 of WO 2015/145131 A1

-

Claim 1

Is it patentable?

The Board discussed the distinguishing features over document D4:

4.1 The Board considers that, among the documents cited in the appealed decision, D4 represents the closest prior art, as it is the only document that suggests using a user device, namely the user’s mobile phone, as a card reader in the context of online transactions, with the aim of addressing the typical problems associated with card-not-present payments (see sections 5.4 to 5.6, in particular page 132).

4.2 However, unlike claim 1, the user’s phone in D4 functions as a token reader: during a transaction on the merchant’s website, the user is prompted to present their card to the phone, which reads the card and generates a dynamic code. This code must then be manually entered by the user into the website, which forwards it to a verification host (corresponding to the claimed payment service host) for authentication (see Figure 5.6). In other words, the phone supports user/card authentication, but does not act as a Point-of-Sale (PoS) terminal capable of completing the payment transaction by directly communicating with the payment service host.

4.3 Accordingly, claim 1 differs in that:

1) The payment service host receives a payment request identifying a specific user device for a transaction with the merchant and retrieves a corresponding user device profile, which includes routing data for communication with that device.

2) The payment service host retrieves a PoS configuration profile associated with the merchant and sends a corresponding PoS configuration to the user device based on the routing data.

3) The user device configures a PoS terminal application within a secure element based on the received PoS configuration, enabling it to act as the merchant’s PoS terminal and complete the payment transaction by communicating directly with the payment service host.

The Examining Division had considered these features to be non-technical:

4.4 The examining division considered the PoS configuration profile to represent a set of business rules or preferences defined by the merchant. They also held that deploying such preferences to the user device as in features 1) to 3) was a straightforward implementation of a non-technical business requirement on a generally known payment system architecture.

However, the Board disagreed:

4.5 The Board takes a different view. While the abstract goal of avoiding the transmission of card data to the merchant may come from the business person, features 1) to 3) define a specific technical solution for achieving it. In particular, the payment service host is configured to retrieve a PoS configuration associated with the merchant and to send it to the user device, which then configures a secure application accordingly. This enables the user device to read card data and communicate directly with the payment service host to complete the transaction.

These steps involve modifying the existing system infrastructure, including how the user device is configured and integrated into the payment flow. Such changes require technical knowledge of the system architecture and fall within the expertise of the technically skilled person – not the business person, who may define the desired business objective but lacks the competence to specify the structural and functional changes needed to implement it (T 1463/11 – Universal merchant platform/CardinalCommerce, T 1749/14 – Mobile personal point-of-sale terminal/MAXIM, point 5).

The Board therefore concludes that features 1) to 3) contribute to the technical character of the invention and must be assessed for obviousness in light of the prior art.

While the Board did not wholly agree with the technical problem formulated by the applicant, it still considered the subject-matter inventive for the following reasons:

4.6 The appellant argued that features 1) to 3) enhanced security by ensuring that the card data was sent directly from the user device to the payment service host, thereby bypassing the merchant.

The Board is not convinced that this results in a security advantage over D4. In D4, a unique dynamic code is generated from the card data by a cryptographic module for each transaction (see sections 5.5 and 5.6 of D4). Since the merchant receives only this code, the card data likewise remain protected from the merchant.

4.7 Thus, features 1) to 3) rather provide an alternative online transaction system in which the user’s payment card data are not shared with the merchant.

Starting from D4, the Board does not see how the skilled person would arrive at the solution of claim 1. While the Board agrees with the examining division that the remote provisioning of software on user devices was generally known at the priority date, there is no apparent reason, except in hindsight, to change the user device’s functionality so that it acts as a PoS terminal directly completing the transaction.

Therefore, the Board considered that the subject-matter was inventive.

More information

You can read the full decision here: T 1392/20 (User device configured to function as PoS terminal/HILLOA) of July 15, 2025, of the Technical Board of Appeal 3.5.01.

Preston is a European patent attorney at BARDEHLE PAGENBERG. He handles patent applications in the field of electronics and communication technology, particularly hardware and software inventions related to wireless communication and entertainment devices.