The patent relates to delegating access decision evaluation for building automation. The Board considered that sending a specific access policy was insufficient for technical effect, and a device-specific access policy using context attributes as variables lacks technical character, since the policy itself need not be based on technical considerations. However, the Board acknowledged that the hybrid approach of delegating the access control decision to the accessed device was technical. Thus, certain claims were considered inventive compared to the others.

Here are the practical takeaways from the decision: T 0588/22 (Access decision evaluation for building automation and control systems/SIGNIFY HOLDING) of May 28, 2025 of the Technical Board of Appeal 3.5.06

Key takeaways

The invention

The Board defined the invention as follows:

4.2 The invention relates to a building automation and control system (BACS) comprising access decision evaluation, i.e. deciding whether a certain device should be allowed to communicate with or otherwise interact with another device in the system; see page 1, lines 9 to 20, and page 3, lines 21 to 29.

4.3 The invention is aimed at improving the information security of such systems, in particular access control in the sense of authentication (who you are) and authorisation (what you are permitted to do); see page 3, lines 17 to 20. One limitation on improving access control is the delay (latency) such measures introduce between a user giving a command and the system reacting. The invention seeks to reduce latency by combining an initially centralised approach, which offers high scalability, with a subsequently distributed approach, which offers reduced latency; see page 2, line 23, to page 3, line 10. This has been referred to in this case as the “hybrid” approach.

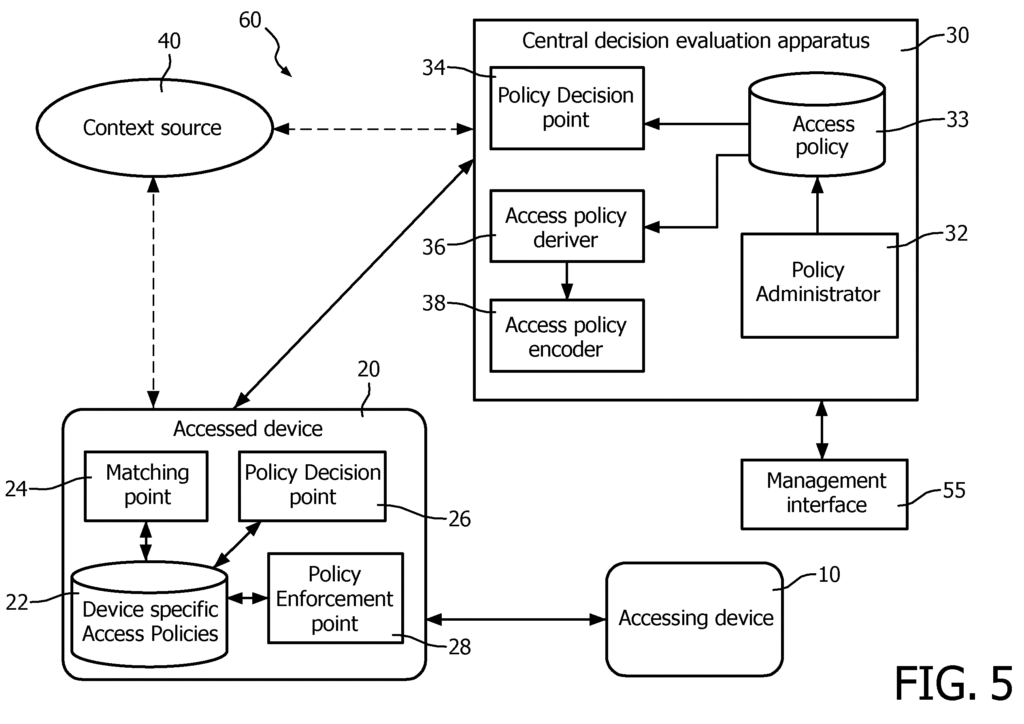

4.4 As illustrated in figure 5, an “accessing device” (10)(defined on page 4, lines 4 to 8), for instance a smartphone, sends an “access request” (20) to an “accessed device” (defined on page 4, lines 9 to 13), for instance a lighting device or electronic lock. The accessed device in turn sends an “evaluation request” to a “central decision evaluation apparatus” (30) which decides, based on one or more “central access control policies”, whether the access request is to be granted or denied. Figure 6 shows a sequence diagram of the information flows in the system. “Policies” are defined as a “set of criteria for the provision of access to resources”; see page 3, lines 30 to 31.

4.5 The central decision evaluation apparatus derives a device-specific access policy from one or more central access control policies and sends this, together with its grant/deny access decision, to the accessed device, the “device-specific access policy” being stored in the accessed device.

4.6 When the accessing device subsequently sends an access request to the accessed device, the latter checks whether the access request matches a stored device-specific access policy and, if so, decides whether to grant or deny the request, based on the stored device-specific access policy without reference to the central decision evaluation apparatus.

4.7 A key difference between the “distributed approach” to access control, shown in figures 1 and 2, and the “centralised approach”, illustrated in figures 3 and 4, is that the latter has a separate central decision evaluation apparatus (30). The “hybrid” approach of the invention, shown in figures 5 and 6, combines the “distributed” and “centralised” approaches (see page 10, line 1, to page 14, line 15) in that it initially uses the “centralised” approach, but then switches to the “distributed approach”.

Fig.5 of WO 2013 128338 A1

-

Claim 1 (Allowed)

-

Claim 7 (Allowed)

-

Claim 9 (Not allowed)

Is it patentable?

The Board discussed then discussed the inventive step of Claim 9:

10.1 Claim 9 of auxiliary request 1 starting from D1

10.1.1 The subject-matter of claim 9 of auxiliary request 1 differs from the disclosure of D1 in further comprising:

a. an access policy deriver arranged to derive from the one or more central access control policies that were used for the evaluation a device specific access policy,

b. wherein the central decision evaluation apparatus is arranged to send the decision and the device specific access policy to the accessed device (20).

10.1.2 In the oral proceedings the respondent argued that sending the decision and the device specific access policy to the accessed device (feature “b”) had the technical effect of enabling the hybrid approach, since the accessed device could only decide itself if it had the device specific access policy. It was moreover not usual to send rules to another system element.

10.1.3 The appellant argued that the features of the central decision evaluation apparatus were not limited by its effect on another system element, namely enabling the accessed device to decide. Moreover the access policy could be based on purely financial rather than technical considerations.

10.1.4 The board finds that sending the decision and the device specific access policy to the accessed device is a necessary but insufficient condition for the presence of a technical effect in the central decision evaluation apparatus, since the criteria in a policy need not be technical. The derivation of a device-specific access policy and the taking of a decision based on it can be non-technical steps which are thus unable to lend inventive step to the claim. For instance, sending the derived policy together with the decision could merely serve the non-technical purpose of informing the accessed device about the reasons for the decision taken.

10.1.5 Hence the subject-matter of claim 9 lacks inventive step in view of D1.

However, the Board considered that claims 1 and 7 were inventive for the following reasons:

10.2.8 The board finds that the subject-matter of claim 1 of auxiliary request 5 differs from the disclosure of D1 in the following features:

a. the method takes place in a building automation and control system;

b1. deriving, at the central decision evaluation apparatus, a device-specific access policy from one or more central access control policies that were used for evaluation;

b2. sending the device-specific access policy from the central decision evaluation apparatus to the accessed device and storing it there and

b3. sending, from the accessing device to the accessed device, a subsequent access request, evaluating, at the accessed device, whether the subsequent access request matches the device-specific access policy stored in the accessed device, if so, deciding, at the accessed device, whether the subsequent access request is granted or denied based on the device-specific access policy.

10.2.9 The board does not accept the objective technical problem proposed by the appellant. From the perspective of D1, this formulation would require the skilled person to start from a known solution in a medical context and, in a way, to look for a problem, namely an automation domain which might profit from that solution. However, a central assumption of the problem-solution approach is that the skilled person starts with a problem and looks for a solution to it. The board also notes that the appellant has not justified the proposed objective technical problem in any other way.

10.2.10 The board finds that in claim 1 features “b1” to “b3”, representing the so-called “hybrid” approach, would not have been obvious to the skilled person starting from D1. More specifically, although the hybrid approach, i.e. delegating the access control decisions to the accessed devices, has a clear advantage in a building automation and control system, which the board accepts (see above, point 6.2.2) must be construed as having a large number of “accessed devices” such as locks or lighting devices, no such advantage is apparent in the system of D1 in which there is only one, central accessed device. Furthermore, the skilled person would also have no reason to try applying the solution of D1 to such a building automation and control system. Inversely, it has not been argued that, and it is not apparent to the board why, a skilled person starting from, and addressing a problem in, a generic building automation and control system would look for a solution in a medical automation system such as that of D1.

10.2.11 Hence the subject-matter of claim 1 involves an inventive step in view of D1. The same applies mutatis mutandis to claim 7.

The Patentee amended claim 9, but they were also considered not inventive:

10.4.3 The board finds that neither auxiliary request 2 nor 3, nor their combination in 4 introduces amendments lending inventive step to claim 9 of auxiliary request 2 or claim 7 of auxiliary requests 3 and 4. In auxiliary requests 2 and 4 the restriction of the device-specific access policy to only the relevant rules valid for the accessed device seems to be a usual matter for the skilled person of conserving memory space and network bandwidth and, given that the policy need not be technical, the additional feature lacks technical character and is thus unable to contribute to inventive step. Turning to auxiliary requests 3 and 4, the derivation of the device-specific access policy using context attributes as variables lacks technical character, since the policy itself need not be based on technical considerations.

10.4.4 Hence the subject-matter of claim 9 of auxiliary request 2 and claim 7 of auxiliary requests 3 and 4 does not involve an inventive step, Article 56 EPC.

Therefore, the Board considered that although claim 9 was not inventive, the subject-matter of claims 1 and 7 was inventive.

More information

You can read the full decision here: T 0588/22 (Access decision evaluation for building automation and control systems/SIGNIFY HOLDING) of May 28, 2025 of the Technical Board of Appeal 3.5.06